My Pathtracing Journey: Part 2

Hello! In this second devlog I outline what I’ve been adding to the pathtracer for the past 4 months.

If you haven’t seen Part 1, and would like to know more about the project, you can check out the previous blog post and the public GitHub repository for the project.

The great overhaul

In the previous blog post I mentioned that this project is a CPU-based unidirectional pathtracer. Well, that has finally changed with the move over to the GPU! More specifically, I’m using an OpenGL compute shader that gets dispatched in 8x8 workgroups, with each invocation within each workgroup calculating the radiance for a single pixel.

This has resulted in realtime-ish performance, even by just copying all the CPU code to GLSL shader code! What I waited for minutes to be rendered, now renders within a few seconds. The rendering is done as a rolling average of consecutive frames, so each frame has a sample count of 1, but they get averaged out with a weighted average.

Of course, just copying the CPU code to GLSL and hoping for the best isn’t the only thing I did. After extensive profiling with the very useful NVIDIA Nsight Graphics graphics profiler and debugger, I managed to considerably optimize the shader code! This has been a wonderful opportunity to dive into the inner workings of the GPU and learn the different shader stages, as well as more lower-level concepts like Speed Of Light (SOL) usage, how L1 (TEX) and L2 caches work, and more.

The performance is still not up to the level I want it at, but it is mainly hindered by the incoherent nature of pathtracing, where a ray can bounce wherever and make incoherent memory accesses to the GPU’s global memory where the scene geometry, materials and BVH data are stored. I plan on using an existing library for BVH generation, traversal and updating that is optimized for the GPU (like for example Radeon Rays) in the near future.

Here is render of a moderate-detail robot on the GPU. The performance is not perfect, but it is better than 5-10 minutes per render for simple scenes!

Taking a step back

As I said above, I plan to defer the BVH construction and traversal to a GPU-optimized library. This is because I realize that this is a part of the project that I can’t realistically reinvent myself and have comparable performance, while also learning about light transport concepts in parallel. Because of this decision, I wanted to improve my materials before continuing with more advanced models and scenes. By materials, I mean more advanced BRDFs, BSDFs and similar.

Up until now I have used the Lambertian and Phong BRDFs, and a dirac delta function for the perfect mirror specular material. These materials are better than nothing, and a great starting point, but in order to model more realistic materials, I set out to learn about microfacet theory.

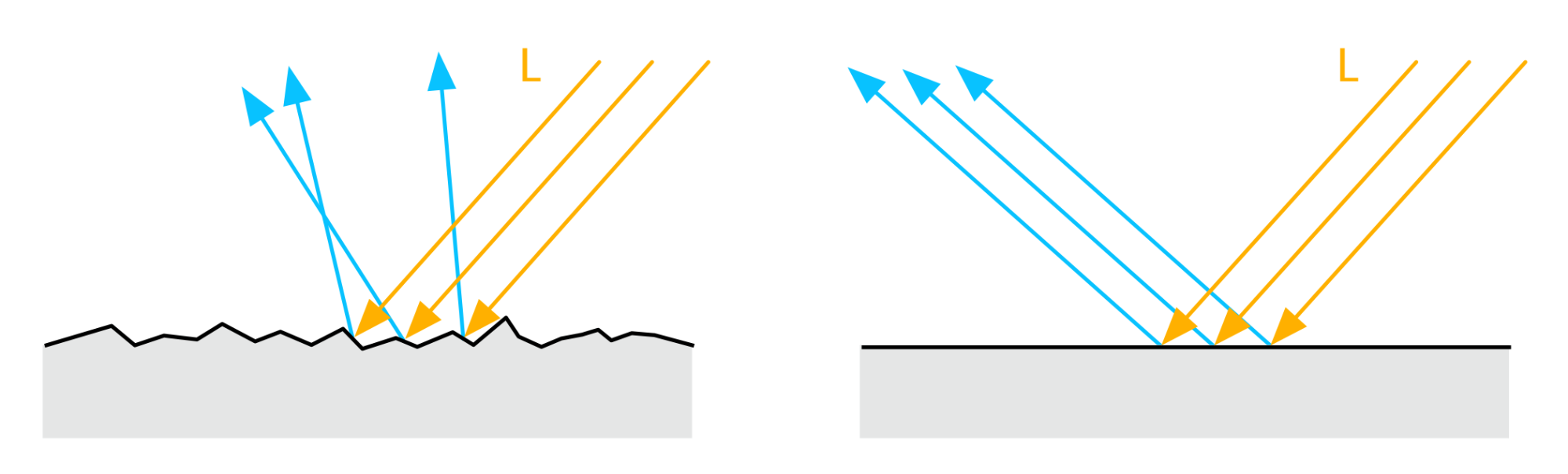

Microfacet theory is a more advanced model of looking at an object’s surface, where the surface is neither completely rough nor completely smooth, but is modelled by microgeometry in the form of bumps and peaks on the surface. This model is still an approximation, as it assumes 1) nanogeometry is completely smooth or completely rough, 2) light is modelled via geometric optics as a ray instead of as a wave, and 3) the microgeometry is a heighfield (no caves or overhangs).

Without going into too much detail in the math, a microfacet-based BRDF is defined by its distribution of microfacet normals (what distribution of microfacets have normals facing a certain direction), the geometry of the microfacets (do microfacets shadow other microfacets, do they occlude other microfacets from the viewer), and a term that increases reflectance at glancing angles (Fresnel).

I haven’t delved too deep into microfacet theory apart from learning about the general material types (metals, dielectrics and semi-conductors), how they reflect, refract, absorb and scatter light, and some intuition behind the different terms in the general microfacet-based BRDF. I’m still learning and implementing different materials. But, I do have one material to show, and that is the Oren-Nayar BRDF.

The Oren-Nayar BRDF is a microfacet-based BRDF that models V-cavities as the microfacets on the object’s surface and a completely Lambertian micro-BRDF (the BRDF for each microfacet). This means that the Oren-Nayar BRDF models local subsurface scattering (where the absorption and scattering within the surface is within distances smaller than the simulation length - AKA the pixel size), which results in light getting scattered diffusely. It is commonly thought of as a more general version of the Lambertian BRDF, as it models surface roughness. Lambertian is a model of a diffuse surface with 0 roughness, while Oren-Nayar can model higher roughness values.

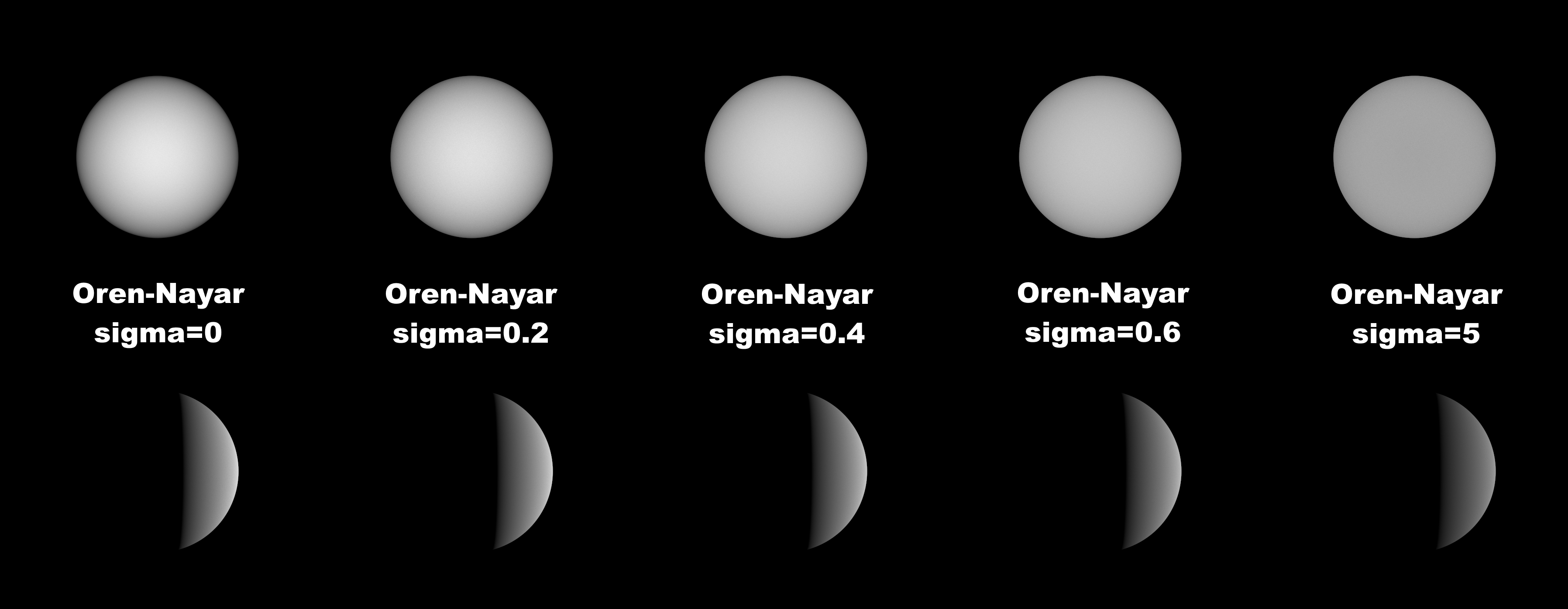

Below is a comparison between different roughness values for Oren-Nayar, in a given test scene where a sphere is lit by an extremely small point light, rendered by my pathtracer.

And here is a video showcasing an environment map as a replacement for a static background radiance value, as well as an array of spheres with increasing roughness values, using the Oren-Nayar BRDF. Excuse the YouTube compression, use the highest quality when viewing :)

NOTE: there is some energy loss with increased rougness, which is expected as the approximation that the original Oren-Nayar published doesn’t account for interreflection between the microfacets, which results in terminating rays that might get scattered after the first bounce towards the enviroment. Multiple scattering is needed, or at least simulating the first couple of secondary bounces.

What’s next?

As I mentioned, the current priority is to implement more microfacet-based materials such as a metallic material, plastic material and similar. As always I try to not speed through these things as understanding the math behind the implementation helps a lot during reading subsequent papers and debugging the implementation, so the velocity of development is not the biggest!

After that, again, I want to implement a BVH library that’s been optimized for the GPU. This will allow me to use higher-fidelity models and improve my model loading to automatically detect material types and use the appropriate BRDFs.

Stay tuned for blog posts on my Twitter or by subscribing to the RSS feed of this blog! Thanks for reading :)